Yojimbo

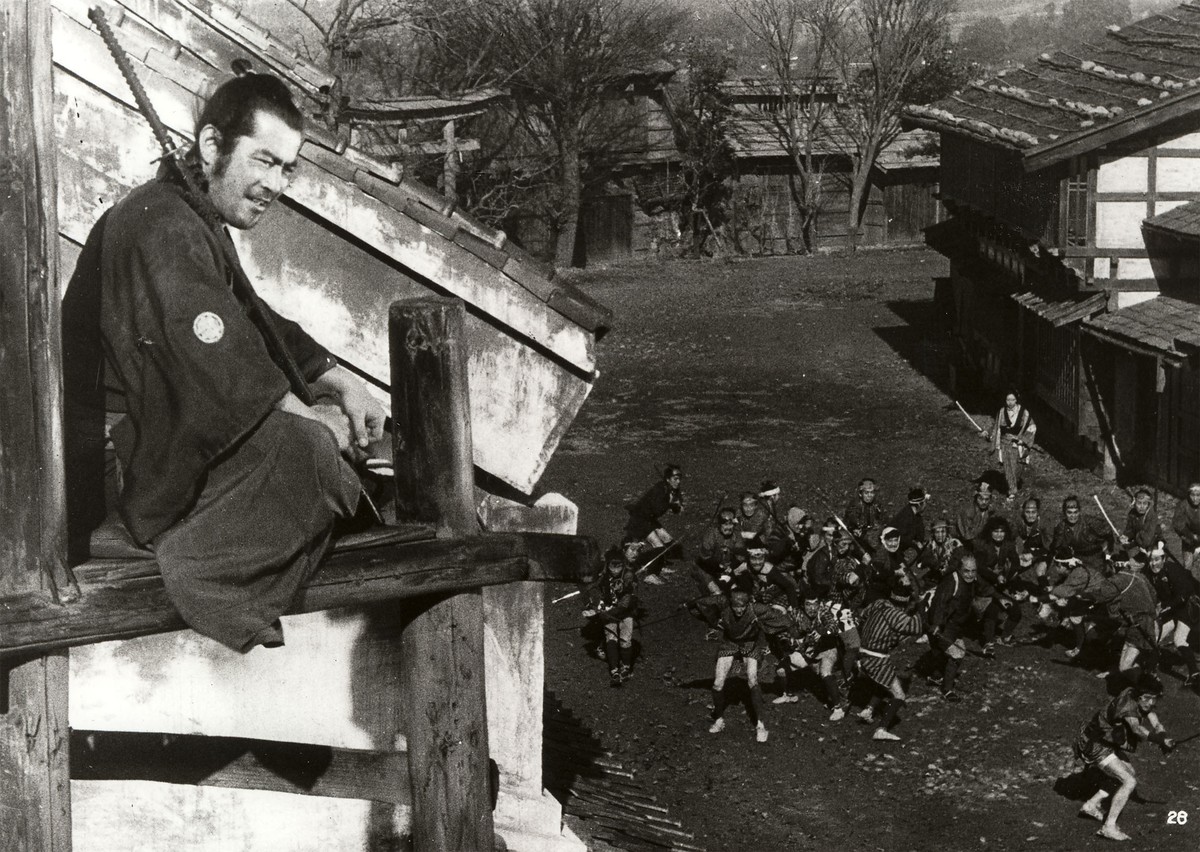

Sanjuro, soldier of fortune―unemployed, unbathed, generally unprincipled, with only the threadbare clothes on his back and his razor-sharp swords. But vagrant as he sees, his faded garments bear the crests of a samurai, labeling him as a member of the superior, warrior class. His wandering takes him to a foreboding village, one under the yoke of two gangs―bitter rivals―who are constantly at war with each other. Decent citizens are too terrified to venture into the streets, and the police are helpless. In short, the community epitomizes the corruption and violence of the era―the early 1860’s. Sanjuro is soon goaded into fighting with some of the local hoodlums, and his prowess with the sword is amply demonstrated. Impressed by Sanjuro’s swordsmanship, Seibei, boss of one gang, offers the samurai a considerable sum of cash to act his bodyguard. And Sanjuro, eager for mane, accepts. Thus, with a champion, Seibei challenges his competitors to a battle, although secretly he and his avaricious wife, who runs a brothel, plan that, after Sanjuro has slaughtered the opposition, they will do away with him and regain his fee. More alert than anticipated, Sanjuro overhears their scheme, resigns his position as the battle begins and scales the village bell tower to watch and laugh, while the two mobs make fools of themselves in a ludicrous yet suspenseful engagement. But suddenly the gangs withdraw, leaving the streets deserted: A team of government inspectors arrive, obliging the town to wear a mask of peace and hospitality. During the lull, Ushitora, boss of the rival gang, offers Sanjuro money to join his forces. At the same time, Seibei retracts his plan to kill the samurai and begs him to reconsider his offer. As the police leave, Sanjuro finds himself very popular. But Sanjuro’s superiority with weapons appears jeopardized, however, when Unosuke, Ushitora’s younger brother, returns to town with a revolver... Eager for excitement―and money―Sanjuro grabs two hoodlums sent by Ushitora to assassinate an official and, aware that what they know could convict Ushitora, sells them to Seibei. He then sells Ushitora news that Seibei is holding the thugs. To protect himself, Ushitora captures Seibei’s son and offers him in exchange for the would-be assassins. When Unosuke decides to shoot the two hoodlums, Seibei is left without hostages, and Ushitora is unwilling to return Seibei’s son without something in exchange. Seibei, then, kidnaps the mistress of a wine-maker, who is Ushitora’s backer, and, when the prize captive is revealed, a quick exchange of prisoners is effected. The wine-maker’s mistress, a beautiful girl, is actually the wife of a farmer, who was forced to relinquish her as payment for a gambling debt. Moved by the farmer’s misery at being deprived of his lawful wife, Sanjuro stages a one-man raid on the place where the girl is kept, kills half a dozen guards and wrecks the premises. He returns the girl to her husband and child and chases them out of town lest further harm befall them. Ushitora thinks Seibei’s mob responsible for the raid and sets fire to the home of the latter’s backer, a silk wholesaler. Seibei retaliates by plundering the home of Ushitora’s sponsor. With a silk at detection, Unosuke, with his ever-present pistol, tricks Sanjuro into revealing himself as the instigator of all the trouble and, as punishment, has him beaten almost beyond recognition by a grotesque giant. Though not far from death, Sanjuro manages to escape to the safety of a farmhouse. He later lets it be known that he has joined Seibei. Ushitora believes the lie, sets fire to Seibei’s home and kills his wife and son. Thus, a war. Wounds healed, Sanjuro appears in town, slices his way through the remnants of both gangs and at last faces the inevitable: Unosuke and his revolver. Though his chances for survival suddenly seem very slim, Sanjuro pulls out a concealed knife and, at twenty paces, deftly buries it in Unosuke’s arm. The sword triumphs over the pistol. Leaving the village a wreck, Sanjuro again strikes out for points uknown.

Festivals & awards

Oscarnomination 1962 Toshiro Mifune, Best Actor

Blue Ribbon Award 1962 Toshiro Mifune, Best Actor

Kinema Junpo Awards 1962 Venice Film Festival

Copa Volpi Toshiro Mifune, Best Actor

Credits

Would you like to show this movie?

Please fill out our form.

Feel free to contact us

Press voices

«Die bestechendste Kadrage, die erregendste Symmetrie, das betörendste Chiaroscuro für die verkommenste aller möglichen Welten. Kurosawa malt im Bilderbuch des Schwertkämpfer-Genres mit grandios beschwingtem Pinsel, in den der Hohn Grandvilles, die Zynik Swifts, der Furor Sam Fullers gefahren sind. Seht da, ein Dorf mit prächtigen Holzhäusern, bevölkert vom Clan des Seidenhändlers und vom Clan des Sakefabrikanten, die einen Hyänen, die anderen Schakale - und jeder erpicht auf die Vernichtung des anderen. Ein reizender Mikrokosmos Japans, der Marktwirtschaft, der Welt. Toshiro Mifune als 'Ronin', herrenloser Samurai, gerät in die Stadt, wird Leibwächter der Schakale, dann der Hyänen, um zuletzt als feixender Profiteur beide Aasfresserparteien gegeneinander auszuspielen. Am Schluss hat teils er die Stadt, teils die Stadt sich selbst befreit, indem sie zum Friedhof geworden ist. Mifune kratzt sich am Kinn, schüttelt den Kopf und verlässt wiegenden Raubtierschritts den entvölkerten Ort.»

Harry Tomicek, Filmmuseum

«Der mit viel Virtuosität und spezifischer Begabung für Bildkomposition gedrehte Film besticht vor allem durch seine Vielschichtigkeit: In die hochgespannte Dramatik der Fabel mischen sich groteske Züge und barocke Übertreibungen; das Genre der Samurai-Filme scheint hier in seine eigene Parodie überzugehen.»

Die Zeit